The Dysfunction of EMS and Tragedy of Foxconn

The company’s handling of a suicide cluster overshadows the context.

Foxconn Technology Group opened its first electronics assembly manufacturing plant in Shenzhen, China, in 1988. Today, that is the company’s largest plant, with 460,000 employees, about 16% of whom live on campus.

Founded in 1974 as a manufacturer of plastic products (notably connectors) by Terry Gou, who remains its CEO and largest shareholder, Foxconn has become the largest contract manufacturing company. But recently, the company has come under public scrutiny due to allegations of employee mistreatment. To date, 12 employees have jumped from company buildings in suicide attempts during 2010; only two survived (in critical condition). Likewise, the company’s critics have leaped to the conclusion that Foxconn mistreats its workers, but the situation demands greater nuance and understanding. This cluster should be investigated, and indeed the government and Foxconn’s customers are doing so. Managers have provided trained counselors in a care center since April and a suicide hotline since last year, which has been expanded significantly amid these tragic events.

The issue has been exacerbated by Gou’s lack of understanding as to why the suicides are happening. Guo recently commented that it is not possible to determine any one cause for these tragic suicides and seems mystified as to why an employee would take their life. The company responds that Gou has been based in Shenzhen since May, leading a team addressing these very complex issues.

The deaths are thought to be related to working conditions at the plant: long hours for poor pay and constant pressure to perform. Indeed, the company’s operations and demanding working conditions (although not nearly as bad as the conditions in China’s coal mines) appear cause for despair. Workers complain about military-style drills, verbal abuse by superiors and “self-criticisms.” They reportedly are forced to read aloud, fined for unwritten abuses (talking to coworkers, tardiness, etc.), as well as allegedly pressured to work as many 13 consecutive days to complete a big customer order - even when it means sleeping on the factory floor.

Foxconn denies these allegations, and claims to follow EICC overtime guidelines of a maximum of 60 hours per month. (The company also says it will abide by China’s pending overtime guidelines of no more than 36 hours per month.) Moreover, the company’s recent wage hikes purportedly ensure that workers will not have reduced wages with reduced overtime hours.

It’s true that Foxconn has done itself no favors. A young manager killed himself last July after an Apple iPhone prototype went missing, and his final messages to friends suggest he had been interrogated and beaten. In a separate incident the following month, the company confirmed its guards beat employees after a video surfaced of the episode. In 2006, after a Chinese newspaper reported that employees were being abused, a charge later shown to be false, Foxconn sued the two reporters personally and sought to have their assets frozen, provoking a public backlash against the company.

Gou’s own lack of awareness has not helped the situation either, although he has made repeated efforts to apologize to the families of the deceased. However, in a recent shareholder meeting Gou announced, “If a worker in Taiwan commits suicide because of emotional problems, his employer won’t be held responsible.…” Such statements seem aimed at keeping the company financially strong rather than honestly facing the core problem.

Suicide results from depression and the belief that there are no other options. Indeed, when a worker comes from the country to work and send back money to their family, and this does not happen, it can be basis for despair. One inside reporter confirmed this by saying that young people frequently come to Foxconn hoping to eventually start their own business or go to college, but most never realize that dream. According to the New York Times, recent interviews with employees said the typical Foxconn hire lasts just a few months before leaving, demoralized.

Sociologists and other academics see the deaths as extreme signals of a more pervasive trend: a generation of workers rejecting the regimented hardships their predecessors endured as the cheap labor army behind China’s economic miracle. While the EMS industry drives productivity to the extreme, and at times can be extremely demanding and punitive, it is not necessarily the cause of despair and hopelessness that sometimes causes people to commit suicide, although it can be a contributing factor.

Regardless, the company could do more to alleviate the conditions for despair and demoralization. For example, on May 27, 2010, the Shenzhen Post related the case of a typical Chinese female worker named Happy, a 19-year-old assembly line worker. She sends back home as much of her 1000 RMB ($150) monthly salary as possible, but with Foxconn’s severe penalties for unwanted kinds of behavior, this dream seems remote. For example, Happy likes washing her own clothes by hand; she claims it calms her in times of stress. Her factory mandates uniforms be dry cleaned, however; if she washes it, she is penalized 500 RMB. If she is late, she is charged 100 RMB per minute. If she refuses or can’t work overtime when needed, she is removed from work lineup for over a month, or until she can come up with the fee for reinstatement. Talking during working hours brings a 100 RMB fine. She even had to borrow money once to pay the negative balance from her salary. Such conditions would leave anyone feeling hopeless.

Subsequently, the rash of suicides has intensified scrutiny of the working and living conditions at Foxconn. Responding to the clamor, Foxconn has offered to double salaries in three months’ time, setting a new standard for many other local companies such as Honda. Moreover, the company is building an enormous safety net in a pathetic effort to stop people jumping to their deaths, but a recent attempted suicide by a young man who slashed his wrists shows that such efforts will not deter those determined to take their own lives.

The gap in recognition of the problem underlying why a person commits suicide was further reflected in Gou’s proposed solution to get all employees to sign a non-suicide pact. Employees have already complained that the letter makes it seem like they could be carted off to a mental hospital if they argue with a supervisor, and that they don’t know what the consequences are if they don’t sign. The company has since been forced to withdraw the letter. In a seemingly final act of desperation, in May 2010, DigiTimes reported that Guo sought the aid of an exorcist to try to put an end to the tragedies. (Foxconn representatives noted this is a common cultural practice in China when a death has occurred.)

Overall, indications are that conditions in Foxconn’s factories are good and job applicants are eager to work there. By in large, most workers are happy to submit to the culture and receive overtime opportunities. Yet, the labor intensity is high and Chinese workers have commented that many Westerners would find it difficult to work at Foxconn. As BBC News recently quoted one employee, “I always smile when I see pictures of Chinese workers asleep at production lines; this is their culture. Chinese are taught from school that lunch time is nap time. The 1.5-hour lunch break is common practice, almost sacred. How often do we have that in the West?”

The problem of ongoing suicides at Foxconn needs to be put in perspective. Twelve people (at last count) seems a lot, but the firm has an estimated 800,000 workers, more than 460,000 of them at a single campus in Shenzhen. According to the World Health Organization, China’s suicide rate is 13 males and 14.8 females per 100,000 people (by comparison, the US has 11 per 100,000). In other words, Foxconn’s suicide epidemic is actually lower than the national average in China and many other countries. Unfortunately, this says nothing about the fact Foxconn is the only EMS company in Asia that seems to be experiencing this problem.

Suicide is too complex an issue to rush to conclusions, and the working conditions in China are improving. For the time being Foxconn seems to be taking its responsibility to its workers’ health seriously and deserves the benefit of the doubt.

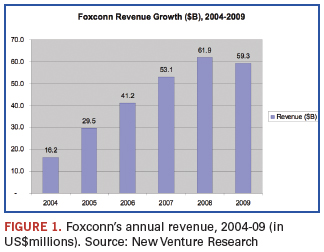

Randall Sherman is president and CEO of New Venture Research Corp. (newventureresearch.com); rsherman@newventureresearch.com. His column runs bimonthly.