2005 Articles

RFID Signals a New Electronics Age

The future may be summed as 'What does it cost to put a tag on a box?'

With major mandates for RFID tag use and double-digit growth projected, RFID tag manufacturing is one of the most exciting areas in electronics. At first blush, RFID tag use aids inventory control and asset management. Yet its potential impact on consumer buying represents a new era for this field. As Kimberly-Clark director of corporate auto-ID/RFID Mike O’Shea told CFO-IT magazine, “It’s not the RFID technology that’s important. It’s the reengineering of the business processes that will deliver value.” Data on purchasing trends, in the hands of makers of consumer products, could influence real-time pricing strategies, distribution methods, the need for warehousing and product manufacturing – not to mention drive software developments and more computing power, servers and data storage. IBM recently announced that it would spend $250 million by 2010 to develop and promote RFID software applications. Other forthcoming software will help manage the immense amount of data generated by increased deployment of RFID.

|

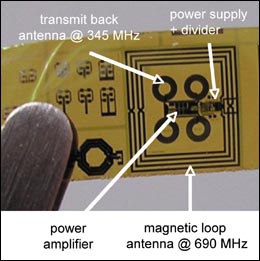

| FIGURE 1: Would you pay more than five cents for this? An RFID tag, with parts labeled. (Source: Philips) |

RFID technology is not new; it has been in development for a dozen years. What is new is the mandate from Wal-Mart that required its top 100 suppliers to provide case or pallet tagged items to the Texas region by last January. While compliance has not been total, the demand for RFID tag capability was clearly stimulated by the mandate. Rather than a technology push, RFID technology is now demand driven.

Millions of RFID tags are in production today. Applications include office security badges, gas stations (ExxonMobile’s Speedpass), auto entry and ignition, ticketing systems and inventory management for retail and military. Expansion relies on a number of factors – and just what the prospects are depends on who is answering the question. For many companies, low-cost tags are the limiting factor in the promised growth of RFID. Others argue that when volumes rise, tag prices will fall.

Many conferences have focused on RFID adoption, but none centered on manufacturing issues associated with the RFID tag and inlay. For this reason, TechSearch International in late March assembled a forum of experts on all aspects of RFID IC packaging and assembly from around the globe to discuss manufacturing issues. One speaker, Rick Koskella of Sun Microsystems, described experiences of Sun’s RFID test center. Another, Dr. Gitanjali Swamy, presented a cost model for RFID based on her work at MIT. Other presentations were from semiconductor makers and inlay manufacturers from Philips, Texas Instruments, Celis Semiconductor, Alien Technology, Symbol Technologies and KSW Microtec. Also, equipment makers including Muhlbauer and Toray Engineering shared their experiences in RFID tag assembly.

One panel looked at challenges to lowering RFID inlay and tag assembly cost. Today’s tag prices range from 15 to 50 cents. Many participants agreed that low-cost assembly of RFID chips and antennae may be the critical roadblocks to attaining a five-cent RFID tag. There was no consensus as to when (or if) a five-cent tag might be reached. However, volume and time remain the biggest obstacles to lower cost tags. Depending on the application, price is not an impediment to the RFID use in high-value products such as pharmaceuticals, autos and military applications. Indeed, Enu Waktola of Texas Instruments asserted that discussion on cost should focus not on component or assembly cost but rather on system cost. According to TI, the focus should be, “What does it cost to put a tag on a box?” Tags that integrate with different sizes and shapes of labels are needed in the end-user application. Users expect consistent performance, and key elements driving system cost are reliability and quality.

As with any new technology, development of infrastructure and standards are critical to growth. Standards are clearly needed, and specifications for providers of materials, equipment and assembly processes would aid the market. Some type of standardization in the straps would be useful, according to several participants. Others commented that reliability standards would be helpful in developing tests that reflect the true environment in which tags would operate. With the move to Generation 2 tags, some participants are concerned that it may be difficult to recover development and NRE costs and adoption may be slowed. However, readers and software are upgradeable and should work in next-generation products. Unlike the earlier version, Gen-2 permits global interoperability via single tags. Previously, RFID tags were country-specific and based on different radio frequencies. There are also concerns that IP claims may impact tag cost. Hopefully, these issues will be resolved.

Even a three-cent tag may not be cheap enough for some item tagging. However, some alternative technologies promise lower cost. Dr. Dan Gamota of Motorola indicated that 13.56 MHz operating frequency for a tag made from organic semiconductors may soon be a reality. While this frequency is not suitable for all applications, the use of low frequency tags for documents and books may be reasonable.

When RFID tag volumes increase and infrastructure matures, the full market potential will be realized. As TI succinctly described, cost reductions require higher throughput and standardized form factors. A common tag accepted worldwide is key. There are no technology limits to building the infrastructure for RFID and the market should reach its full potential in the coming years.

E. Jan Vardaman is president of TechSearch International, Austin, TX; jan@TechSearchInc.com.