Rocket Men

Silicon Valley’s fastest-growing EMS is taking flight.

It’s cliché to say profitability in electronics manufacturing services is not about making better solder joints but rather turns on a company’s ability to manage its supply chain.

Hundreds of millions of dollars have been invested in software and other tools designed to ensure optimum inventory levels and real-time feedback loops. But as an industry we have yet to overcome the wild inventory swings and occasional lead-time fiascos.

One Silicon Valley EMS is edging closer, however. Santa Clara-CA based Rocket EMS is betting its future on homegrown software that oversees every aspect of its operations, from ordering to inventory to line management.

Rocket EMS founder and president Michael Kottke is already something of a legend in the Valley, having cofounded three other successful EMS companies. He’s worked in the industry since he was a child, learning assembly at the feet of his father, Dennis, a successful electronics executive in his own right.

With Rocket EMS, the younger Kottke’s goal was to maximize every moment from end to end, even before an order is received.

“If you can’t process jobs at the front-end, machines sit idle,” he says. “So, it’s a race to how much you can feed a machine. You can set up a factory that could build 50 jobs a day but can’t get programs through the front-end to the line. Take a machine that holds 2,500 parts, and you have 55,000 parts in a stockroom. You have tofigure out how to manage it.

“Machines are so much faster that everything related to the supply chain has to be done in the front-end. The only way to do that is to have an encompassing software.”

Kottke’s solution: Voyager. Voyager is part database, part MES, part best friend. It’s the byproduct of reams of weekly meetings where the team of developers outlined projects, staff and priorities with the goal of one tool to rule them all.

Kottke, whose other passion is motorcycles, draws on racing analogies to make his points. The analytics in Voyager, he says, look at the “best lap” – the optimal configuration of time, inventory, staff and processes – to show where and how to shave off time. “We’re a data collection company that builds circuit boards,” he maintains.

Figure 1. Novel storage practices more than doubled reel capacity.

Figure 1. Novel storage practices more than doubled reel capacity.

Picture Perfect

Another invention is the so-called photo booth. No, the staff isn’t posing for candids. Rather, Rocket worked with a robotics company to build a booth through which it automatically sends every board for imaging. Panels are stitched together and logged into Voyager, where customers can see how it was when it left the plant.

Meanwhile, Voyager is tracking the performance of employees, counting everything from time spent and the number and type of defects tied to each worker. And it collects and collates the photo booth images to help staff understand and correct their defects. Rocket will build five of these, ultimately with conveyors, and install them in strategic spots in the factory, including final inspection and shipping.

About that staff. Rocket employs 255 workers, of which about 230 are in Santa Clara, with the rest in India. Between the Santa Clara and India staff, there are 25 manufacturing engineers and 20 PCB layout engineers. “I could not imagine running a contract manufacturer, especially with our diverse customer base, without an engineering and design group working hand-in-hand 24/7 creating MPIs, machine programs, stencil designs, and every shred of data needed for the manufacturing floor to be successful,” Kottke says. This engineering effort begins the moment they get files from a customer, which eliminates what is typically the biggest front-end bottleneck.

As an example of Kottke’s pride in this engineering capability, he almost brags that Rocket’s stencil costs are 25% more than all its competitors. “We put a ton of engineering into stencils, so we avoid all the touchup by uncontrolled manual labor at uncontrolled (soldering) temperatures. The first one that touches a defect is in final inspection.” Sure enough, our walkthrough revealed no soldering irons near the wave soldering or SMT operations.

Figure 2. The Santa Clara, CA, layout is a traditional straight-line configuration.

Figure 2. The Santa Clara, CA, layout is a traditional straight-line configuration.

Armed with such inputs, Voyager can predict labor costs “so deadly accurate it will hurt your head,” Kottke says. Moreover, the firm can push more material through the front-end to the lines, thus optimizing the capital equipment investment.

Supply-chain management is clearly Kottke’s obsession. In turn, he thinks contract manufacturers don’t build their supply chains to meet the type of product they build. “I would love for a distributor with a lot of money and a lot of pull to sit with me and map out how to make a Voyager-type supply-chain tool. Why can’t Avnet and DigiKey and Arrow get together and say, ‘The customer sends its BoM out to Distributor 1, which supplies X% of the parts, and the others supply the rest. Then you click a button and all the parts come in one order.’ It should be a straightforward thing.” (And lest you think he’s nuts, consider that Amazon does this every day.)

Voyager sits on top of the ERP system now, but in the current year will become a standalone MES. Voyager runs labor reports by customer and can compare the current job to a previous one.

The latest endeavor involves trying to prepare Voyager to start preemptively feeding design issues and schedule changes. A module that handles SMT scheduling by measuring, among other things, takt time generated by SMT programs is in beta. “We have 12 to 15 customers we try to feed information upstream to,” Kottke says. (Of this transparency, Kottke, who is also a walking soundbite, chirps, “If the customers can see the skeletons, you tend not to have skeletons – unless you like the customer beating you up.”)

Voyager is in a constant state of improvement. It tracks employee movements and outputs starting with time in and out and ranging from ESD defects to total scans. Each job is scrutinized just as closely. Events and jobs are color-coded to visually show if an action took longer than it is supposed to. With this level of granularity, Rocket can perform quote models by customer, not department.

“We can see in real-time where we are making money on a job, and there are alerts if the profit level starts dropping,” Kottke explains. “We can tell how long each part number took at each process step and compare that to the Rocket EMS average for that workcell for that customer.” And because Rocket EMS captures an image of each part at incoming inspection showing the lot code, part number and other key details, Voyager will eventually be used to show polarity, which could save 25 minutes on kitting, Kottke calculates. Other add-ons will include all preventive maintenance and employee certifications.

Another novelty: the stock room. Parts are managed by size and shape, not by customer. Doing so allows Rocket EMS to put more inventory in a smaller space. For instance, Kottke says, they increased the number of reels to 3,300 from 1,500 in the same area. The stockroom shelves are 14" wide, able to handle 7" reels back to back. Shelves are geared exactly for size and shape. “We could have 88 different customers on one shelf,” Kotte says. “Different customers’ parts are on the same reel.”

The results are staggeringly effective: “We put 60,000 parts in a location where we once had 25,000,” he notes.

Next up: restocking parts by frequency of use. This is where the engineering really kicks in. Per Kottke’s thinking, every second counts. “If we could save 30 seconds here and there, pretty soon we’ve saved a whole person.”

The 36,000 sq. ft. factory has a traditional straight-line layout, with the stock room at the head, just a couple steps from the lines. (Bulk kitting is performed in a 4,000 sq. ft. building offsite.) The machine mix includes Juki GKC printers, Parmi Sigma-X SPI, Juki pick-and-place, three JT RS-1000 and one Vitronics convection reflow ovens, new Juki FlexSolder selective soldering, and Vitrox AOI on two lines. Three PVA conformal coaters were also added in the past year. Feeder trolleys are staged in front of the lines. This setup has eliminated 35% of the time per line. The goal, Kottke says, is 50%.

Material is tracked through the plant by barcode. RFID would be ideal, but the nature of the high-mix, lower-volume jobs would require too many readers, Kottke says.

Besides the aforementioned inspection equipment, Rocket features Nordson Dage Diamond x-ray with X-plane CT functionality, Agilent i3070 in-circuit test, Spea flying probe testers, and another new Vitrox machine was on order. Inspection is paramount to its quality system. Rocket “x-rays the hell out of everything,” Kottke says, adding the company uses the Vitrox machines to “control” its test operation. “We know every detail of every defect. It’s like we put a manufacturing process into test.”

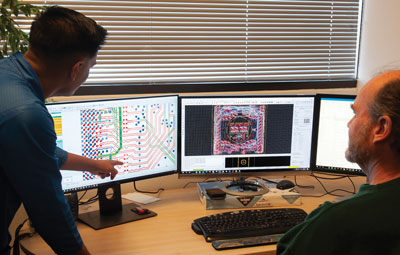

Figure 3. Manufacturing engineers work directly with staff PCB designers to ensure designs are buildable.

Figure 3. Manufacturing engineers work directly with staff PCB designers to ensure designs are buildable.

Constant Motion

In the decade I’ve been following Michael Kottke, I have come to understand he is never satisfied with the status quo. Always on the move, he has pinpointed a site just over the border from California in Nevada, where he would like to build a second factory. He also wants Rocket EMS to start developing its own products. One that Rocket EMS designed is ready for release, and the first customer is expected to purchase nearly 10,000 units.

A second product is an automation product, currently in beta testing. Over time, Kottke says, it will be worth more than Rocket EMS. The new site will use a lot of automation, he thinks.

Then there’s Voyager. Kottke envisions a Web version for staff and a portal for customers.

Since its founding in 2011, Rocket EMS has surged to more than $60 million in annual sales. Kottke has set $100 million as a revenue goal. When we visited in September, Rocket EMS was maintaining 2.5 shifts, and edging toward a third.

For its constant inventiveness and willingness to venture where other EMS companies fear to tread, Rocket EMS is the 2019 CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY EMS Company of the Year.

is editor in chief of PCD&F/CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY; mbuetow@upmediagroup.com.

Press Releases

- AIM Solder Promotes Timothy O’Neill to Vice President of Technology

- AIM Solder Hires Francisco Rodriguez as Regional Sales Manager for Northeast Mexico

- The Test Connection, Inc. Adds Creative Electron Prime TruVision™ X-ray and CT System for Deeper Failure Analysis

- Kurtz Ersa Goes Semiconductor: Expanding Competence in Microelectronics & Advanced Packaging