Exploring the Impact of AI

A special panel discusses the growth of AI tools and its possible effects on the industry.

“Will AI take my job?”

That’s the question on the mind of many around the world today – including electronics engineers and PCB design engineers – and was one of several questions considered during an online panel hosted by PCEA in March.

A group of panelists with notable AI experience – Circuit Mind’s Tomide Adesanmi, Cadence Design Systems’ Taylor Hogan, Zuken’s Kyle Miller, Luminovo’s Sebastian Schaal and Siemens Digital Industries’ David Wiens – gathered to share predictions for the future of AI in the electronics supply chain and answer questions from an audience of industry professionals.

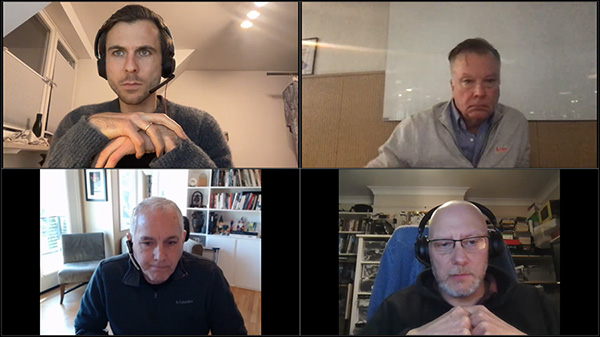

Panelists Sebastian Schaal, clockwise from top left, Taylor Hogan, Kyle Miller and David Wiens discuss the impact AI could have on the electronics industry during a PCEA-hosted webinar.

The 90-minute panel discussion was moderated by Phil Marcoux, who is credited with installing the first surface mount line in the US and is a subject matter expert in artificial intelligence process control and management for electronics assembly.

The panelists opened the discussion by addressing “the elephant in the room” as Marcoux described: Will AI take engineers’ jobs?

Adesanmi gave a definitive answer to the question based on his own work at Circuit Mind, a developer of automated schematic tools.

“My first answer to this is if you think that AI is going to take the job of an electronics engineer in the next decade or so, you don’t really know what an electronics engineer does on a daily basis,” he said.

Adesanmi said he has mainly seen customers using AI tools to get answers and insights faster, such as choosing between Wi-Fi or Bluetooth in a design to stay under a power budget, and then taking those answers into account for their design.

“Engineers are using this sort of AI tool to get a full idea of what they can accomplish very, very quickly,” he said.

Schaal, cofounder of Luminovo, a developer of an AI-driven component sourcing and BoM platform, sees the potential for AI to resolve communication bidirectionally between design and manufacturing.

“If you have a business relationship where an OEM, an EMS and the PCB manufacturer are working together, and they are willing to open their notes, then those profiles can be shifted left into an earlier process ... where designers can then upload their design tool files, and you can see that 360-degree view on the supply chain. That’s something we can provide to the whole design intelligence ecosystem.”

But while AI tools can look at a list of components and requirements to make a list of possible combinations on a board, it still comes down to the engineer to use their own creativity and experience to ensure the design works, Adesanmi said.

“The engineer remains the architect,” he said. “They remain the experts that make this more reliable in our use case, and they remain the verifier of the design in the end.”

Miller, the architect behind Zuken’s new AI-powered ECAD router, echoed Adesanmi’s prediction of at least 10 years before AI has a real impact on design jobs, and he said engineering fields are more likely to be under threat before electronics or design engineers.

“Software, for example, is probably going to be one of the first ones to go,” he said. “And it purely comes down to available data.”

Because there are plenty of examples of code around the internet, AI will have a much easier time training itself, but the PCB design industry’s lack of shared data may prove to be a saving grace for designers, Miller said.

Another factor to consider is that designers’ roles continue to change, said Siemens’ Wiens, who leads a product marketing team and has more than 30 years’ experience in EDA.

The work they are responsible for has continued to increase throughout the years, so engineers will likely be viewing AI as less of a threat to their jobs and more as another helpful tool to help them do their jobs, he said.

Experts say AI will accent, not replace, humans’ roles in electronics design and engineering.

With the demand for electronics increasing and the industry workforce at best staying stable and maybe even decreasing, taking advantage of AI as a toolset may be the only way to keep up with that demand, Schaal said.

“One of our largest customers basically said ‘Look, we see that the electronics manufacturing industry continues to grow, but we just can’t find the people to sustain that growth. The only way we can sustain it is by radically focusing on automation,’ ” he said.

Marcoux also asked the panelists what they would consider to be the “gold ring” of using an AI tool within the industry.

Taylor, a distinguished engineer and product architect at Cadence, said he believes that software is the determining factor in producing better PCBs.

“If the software was better, we could generate more designs quicker for evaluation,” he said. “So my goal in life is to bring the automation of PCB design up to the point where I see design is today.”

He said he doesn’t believe that will reduce the number of designers or engineers, but it will change how they do their jobs.

When looking at a design that a human made, the rules don’t always correlate with the board, he said, and sometimes there is a tribal knowledge about which rules are truly important and which ones work well. Because AI doesn’t have the leeway to make those kinds of decisions, designers will need to do their jobs differently – but that will afford much more productivity.

“I don’t think it’s going to begin with the click of a button and the magic happens,” he said. “I think it’s more like a co-pilot.”

Opening Up to AI

The panel also received questions from the audience, including one that asked what skills could be important for designers to learn to keep up with AI.

Wiens said the easiest way to prepare for the future is to come to it with an open mind.

He said anyone who has been involved in the industry long enough has been a part of a newly-introduced product that has had low adoption – particularly when automation is involved.

“A lot of times it’s because teams have their established processes and, frankly, are too busy to consider new ones. So as a result, opportunity goes by.” he said. “I think having an open mind, thinking about AI as an opportunity, not as a threat, is the biggest thing that designers and engineers can consider as they move forward.”

Adesanmi said he sees two different ends of the spectrum with AI, either as a generalist or as a specialist, and for the best success, engineers should gravitate toward one end or the other rather than stay in the middle.

Being a generalist who has experience in several different fields should allow an engineer to become a supervisor of AI tools who manages processes throughout the production line, but on the other side of the spectrum, there will also be a need for specialists who can handle processes that AI can’t, he said.

“The way I think about it is that if you can put yourself on one end of the spectrum and not dilly-dally in the middle of it, you will probably find a path to the future,” he said.

For many disciplines, the key to lasting in the industry is being willing to change your tool stack, Luminovo’s Schaal said, and while electronics engineers haven’t always had to change their tools as often as others, that looks to be changing.

“I think adaptability is something you desperately need,” he said. “Being able to work with different tools and rethink how you’ve done processes, I think that’s key.”

Cadence’s Hogan also stressed patience as AI grows and develops, and said working with EDA companies that are asking how and why certain designs work will help improve the process and provide a valuable tool.

“This is only going to make you more productive, but you’re going to have to give up the notion that just because it doesn’t look like something you did, it’s not good,” he said.

Ed: The entire panel discussion is available here. To keep up to date with PCEA’s free webinars, sign up for a free membership at pcea.net/pcea-membership-info/.

is managing editor of PCDF/CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY; tyler@pcea.net.

Press Releases

- SMarTsol America Expands Partnership with ASMPT and Strengthens Regional Coverage in the United States

- Absolute EMS Appoints Mark Sika as President to Lead Next Phase of Growth

- Beyond Torque: New Seika Machinery Webinar Reveals How Strain Gage Technology Exposes Hidden Bolt Axial Force Risks in Battery and PCB Assemblies

- New SASinno Ultra-i1 Gives K&F Electronics Added Flexibility in Selective Soldering