Hidden Gems of Printer Management

How lesser-known printer software features can improve process control.

As a process engineer specializing in the stencil printing operation, I understand why many operators are unaware of the bells and whistles in advanced printing platform software – especially when working in a busy production environment. While the primary focus is speed, pressure and angle to ensure the best print at the fastest cycle time cadence, sometimes the production pace can be interrupted by unexpected events. I was reminded of this – and a couple of software tricks – recently when doing evaluation work in our lab.

Our team has been running a process with mixed apertures, the largest of which are 5mm square. During the evaluation, the SPI indicated an occasional paste height failure. The process was not in control, but in an extraordinarily random way. Examining the boards under a microscope revealed large drops/deposits of paste sitting on some of the perfect, uniformly printed deposits; extra material that looked like it had just been dropped on top of an otherwise well-printed deposit. This was causing the SPI to flag the extra height/volume. No pattern was identifiable, so more analysis was required to uncover the root cause. Further investigation revealed material building up on the back side of the squeegee blade.

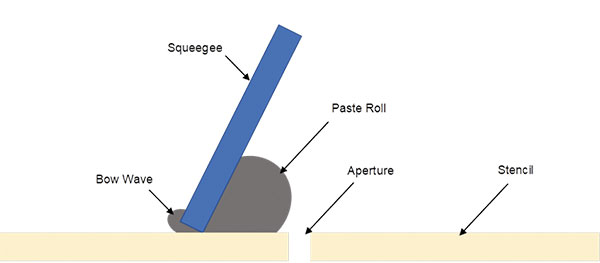

Typically, if the boards being printed are made up exclusively of smaller devices, the squeegee blade goes across the apertures and hits the metal web of the stencil, which tends to seal everything quite nicely. The squeegee blade acts as a hydrodynamic pump, and with so much pressure and when printing large apertures, material can move underneath the blade and collect on its back to form a bow wave (FIGURE 1). This phenomenon is exaggerated when apertures are larger, and in this case, we had small apertures alongside larger 5mm x 5mm openings. When the paste buildup reaches a critical mass on the back of the blade, that material will shear off and drop onto your skillfully printed deposits. This is precisely what was occurring in our evaluation.

Figure 1. A bow wave can appear when extra material moves underneath the squeegee. If not removed, unwanted solder paste may randomly fall onto otherwise well-printed deposits.

The fix? Most stencil printing equipment software have a feature that tells the squeegee to do a short hop backwards under a small amount of pressure – the parameters of which can be specified – and clean the back of the blade of any residual solder paste buildup. The subsequent move forward puts the material back in the paste roll.

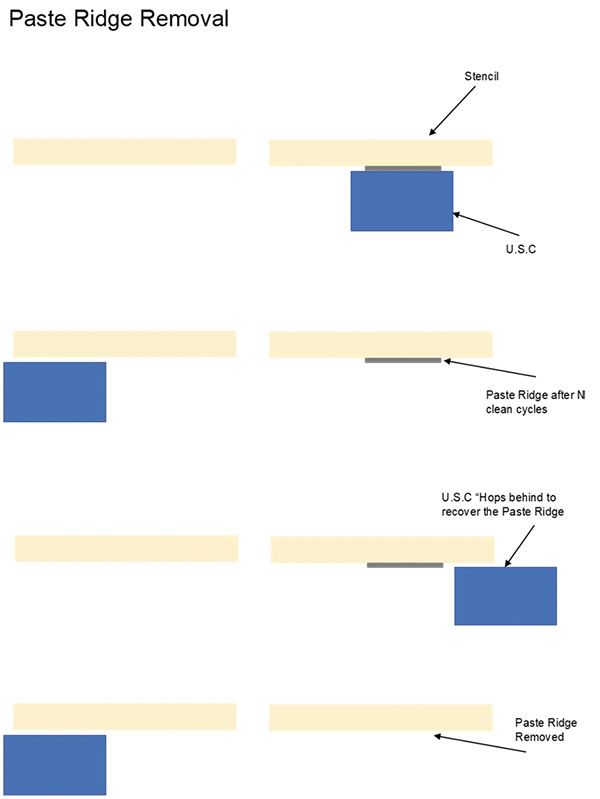

The back of the blade isn’t the only place that material can accumulate, however. This can also happen on the underside of the stencil. Fortunately, there is a similar remedy. In the understencil cleaning operation, the cleaner/cleaning head returns to the same position once it runs its cleaning routine between prints. While in operation, the cleaner pulls material out of the apertures and onto the fabric. When the cleaning head stops at its resting position, a buildup of solder paste material can occur on the underside of the stencil in that area. If not corrected, a ridge of paste grows and can impact print performance.

Much like the remedy mentioned for the extra paste on the back of the blade, there is a software feature that allows lowering of the understencil cleaning plenum to drive a bit farther and clean the material ridge (FIGURE 2). For manufacturers that clean between every print – and there are more than you think, particularly those building mobile devices – this buildup may happen sooner rather than later and result in a nonuniform process. Like paste recovery, ridge removal can be programmed into the software at preferred intervals and align with the process cadence.

Figure 2. Solder paste may accumulate at the edge of the underside of the stencil after numerous cleaning operations. A programmable software feature permits the cleaning system to remove the paste ridge at set intervals, as determined by the operator.

These simple functions, which operators often overlook or are unaware even exist, are handy solutions to ensure the process is controlled. Although both these software features – available on many stencil printing platforms – may add a couple of seconds to cycle time, it’s certainly better than adding potential defects to the process. •

is global applied process engineering manager at ASMPT (asmpt.com); clive.ashmore@asmpt.com. His column appears bimonthly.

Press Releases

- Kurtz Ersa Goes Semiconductor: Expanding Competence in Microelectronics & Advanced Packaging

- ECIA’s February and Q1 Industry Pulse Surveys Show Positive Sales Confidence Dominating Every Sector of the Electronic Components Industry

- Hon Hai Technology Group (Foxconn) Commits To New 5-Year Sustainability Roadmap Through 2030

- Amtech Electrocircuits Navigates Supreme Court Tariff Ruling