How Lean is The Internet of Things?

Using multiple approaches to gather SMT data is inherently wasteful.

What do people really think when they hear the term “Internet of Things?” The Internet carries with it varying perspectives and experiences, meaning different things for different people. The term Lean has been around a lot longer, but also carries the same issue – there is no single consensus of understanding of what it is.

This is not unexpected; there are many points of view from people with different roles. What is important, however, is that we perceive the real value and worth of these innovations, joining them to create a better operation. SMT production represents a real challenge in this respect, but, done properly, there is a real opportunity to get to raise one’s competitiveness and profitability.

The Internet started as a series of simple websites, offering information from one source to everyone else. As we have experienced, the quality of this information varies extensively, coming from different sources with different levels of understanding and experiences. The Internet is simply the conduit to make the information available. It is left to the intelligence of the reader to sort out what is useful and what is not. This view, however, represents the “Internet of People,” rather than the Internet of Things.

Deriving information from machines and automated processes should not be affected by subjective elements such as opinions and philosophy, but rather should simply contain specific, appropriately detailed, accurate and timely information. We otherwise end up with an “Intelligence-deprived Internet of Things” (IdIoT). The value of this definitive information from “things” could be quite significant. If we trust the information, then we can permit it to manage and govern our operation, to an extent, without human intervention. This provides the opportunity for automation beyond the simple mechanical layer that has been the focus of attention in the past.

The term Lean is correctly interpreted as being the removal of all waste. The challenge with Lean is to know how to apply this simple mantra. Projects that focus on an entity, performing “value stream mapping,” will find and expose as many of the improvement opportunities as possible. These projects are often, however, not worth as much as anticipated where certain key elements external to the project may have been overlooked. Lean projects can become too specialized, unable to adapt to changing situations, and may not fit the context in which the process is used in the factory. “Lean components” work best in “Lean machines.” The most important element of Lean that sets the context for Lean analysis, but is often overlooked or at least is underestimated, is the aspect of the “pull signal.” This is the communication mechanism between processes that can be used to determine minimum commitment; that is, don’t do anything until you need to. It is otherwise, by definition, a waste.

The link then between the “Internet of Things” and “Lean” is the ability for the information taken from processes to be used in an automated way to create the “pull” signal for Lean. In the SMT environment, were we able to get information from all of the machines and processes in the way that the “Internet of Things” suggests, then there are some very significant benefits that could be realized. These include Lean materials, planning, engineering, maintenance, new product introduction, and many more, each of which we will explore in detail in forthcoming columns. The benefits that we will discover are not only targeted at the internal operations in the SMT and assembly factory, but also at permitting the factory to reduce costs and delays associated with the distribution chain, between goods coming off the production lines and arriving at the customer. This enables the factory to support the changing needs of the business as a whole, in a significant way.

To imagine how to apply the IoT to the surface mount environment is quite a challenge. The need for data collection from SMT has been around since the machines first came along. It started with manual data collection, simply in terms of counting product completions, from which throughput and productivity were calculated in a crude way. Manually collected data are hardly detailed, accurate or timely and have been a needless distraction to production operators. As more data from SMT were required in an increasingly timely fashion, several attempts have been made to establish industry standards.

Unlike the semiconductor industry, SMT machine vendors paid little attention to this need from their customers. Cross-industry and cross-vendor approaches such as IBM’s Map and Top, GEM-SECS, and more recently CAM-X, among others, have appeared but have all failed to find adoption as a standard. Most likely because of industry competitiveness, machine vendors have instead recently started to use the SMT machine communication ability as leverage to support the sales of the latest platforms of their machines, effectively trying to tie in customers to a single machine vendor. In most cases, however, factories need the flexibility of having machines from a minimum of two vendors (which also ensures “Lean pricing”).

Going forward, the solution for the IoT relies on third parties working closely with SMT machine vendors to extract the necessary live transactional information. This is a two-layer approach involving first the conduit to the machine – that is, the interface itself – and then the interpretation and normalization of the format and meaning of data that are collected, in a way that needs to be increasingly intelligent and real-time. To do this in a complete, accurate and reliable way is no mean feat, and it is adequately maintained by very few third-party vendors in the market. The potential benefits, however, of the IoT together with Lean are really picking up momentum, and will not be ignored, so it is something that needs to be lived with, for now.

Next time, we look into Lean factory flow.

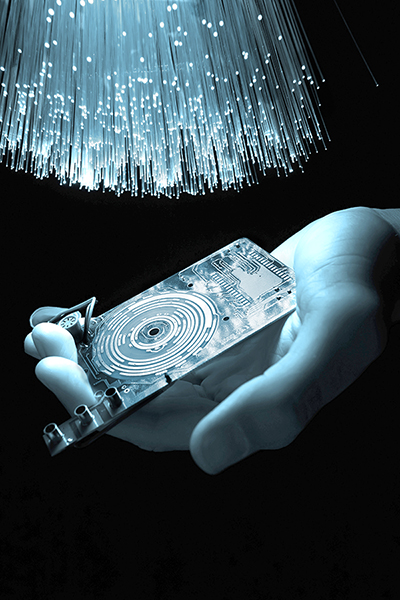

Figure 1. Live information can automatically “pull” products and related resources through production in the most lean and efficient way.

is marketing development manager, Mentor Graphics (mentor.com); michael_ford@mentor.com.

Press Releases

- Green Circuits Strengthens Real-Time Manufacturing Control with Cetec ERP

- Keiron Advances Digital Solder Printing Adoption with New England Expansion Through Yankee Soldering Technology

- Microboard Makes $1.3 Million Investment in Mycronic's MYTower 7+ and MYTower 6X Inventory Towers

- TSMC accelerates fab construction with up to 10 facilities targeted for 2026