Features Articles

Working unconventional hours in remote locations disrupts business more than material shortages.

As we enter the third year of our pandemic-altered world, more chains are strained than just supplies. With people working remotely during odd hours, changing careers, or stepping out of the workforce altogether to care for loved ones, the basic chain becoming strained is communication.

Communication has been transitioning over the past couple decades. Time, culture and technology have dramatically transformed. Long gone are the storied two-martini business lunches where colleagues, customers and suppliers met, broke bread and discussed one-on-one issues that needed ironing out. Over the past decades, face time (not FaceTime) with any business client has become extremely difficult to arrange. Today with Covid, meeting face to face is all but impossible for many. Long-changing trends compounded by recent events have had a negative impact on the ability to communicate effectively, which in turn has strained the quality of relationships in too many cases.

For years, a typical customer service or salesperson would spend so much time on the phone with clients, they were jokingly referred to as having “cauliflower ear.” The ongoing constant chatter between people – most business, but some social – helped build strong relationships. How times have changed. The phone-savvy businessperson and bonding over long lunches are no more. Over the past two decades, email has become the communication vehicle of choice. And the pandemic scattered employees, customers, suppliers – everyone – to remote offices, usually in their homes, hopefully with a quiet room from which to log on to Zoom, GoToMeeting and WebEx.

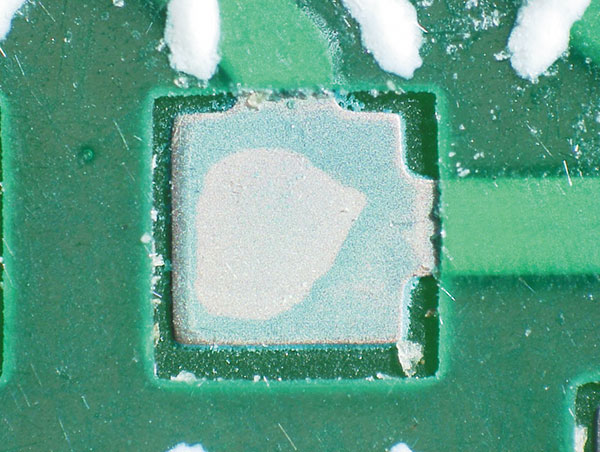

A look at solder mask contamination on pads.

This month we look at solder mask contamination on pads. FIGURE 1 is a very, very bad example that never should have made it to the customer. Solder mask residues are visible on the surface and around the edge of the pad. There is also a level of solder mask undercutting.

FIGURE 1. Solder mask residues.

This would not be acceptable per any standard and would have shown complete nonwetting during soldering. This would have led to a bad day in the office for the assembly engineer or, more important, the shop floor staff.

We have presented live process defect clinics at exhibitions all over the world. Many of our Defect of the Month videos are available online at youtube.com/user/mrbobwillis. Find out how you can share our new series of Defect of the Month videos to explain some of the dos and don’ts with your customers via CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY: https://bit.ly/3mfunlF.

is a process engineering consultant; bob@bobwillis.co.uk. His column appears monthly.

Or how the metaverse will save us, one contorted axiom at a time.

Ambrose Bierce, of sainted memory, is known for a Devil’s Dictionary, a cynic’s primer on human behavior, laid out in Noah Webster style.

Pity he strayed into hostile territory in bandit-infested Northern Mexico in 1913, never to be seen again. Maybe someone lurking in the sagebrush took offense at imagined slights in the Dictionary. People are so thin-skinned.

Pity also that he lived one hundred years too soon. Bierce missed his moment. Obfuscation has exploded, rivaling worthless college degrees (or maybe because of them). A euphemistic pandemic with no known vaccine, for which we need a new dictionary, has infiltrated our lexicon. Straight talk in professional settings is frowned upon, covertly if not overtly. Blunt talk is often memorable and career-threatening. Verbal mush is benign and soon forgotten. As the author of the Bartleby column in the Nov. 20, 2021, edition of The Economist noted, concerning contemporary biz-speak, “People rarely say what they mean, but hope that their meaning is nonetheless clear. Think Britain, but with paycheques. To navigate this kind of workplace, you need a phrasebook.”

How prepared is your organization?

Here we are in January 2022 with a future fraught with more uncertainties than any other during my six decades in the PCB, IC fabrication and assembly industries.

Business is strong despite shortages in labor and parts. Prices are rising, dramatically in some cases. Profits are being squeezed. Rapid government changes in travel restrictions and worker conditions seem endless due to the continuing evolution of the pandemic.

Supply chains are under pressure from a variety of events and circumstances. These include some brief power shutdowns at plants that produce wafers and PCBs in China, chip and other component shortages, shipping issues with a backlog of over 100 cargo ships carrying, for example, container loads of copper-clad laminates anchored off the Southern California coast waiting to be unloaded. The battery industry is gobbling up copper supplies. Major consumers are buying into chipmakers who can guarantee their needs. This affects those who cannot, causing them to scramble for new sources.

Not only are ICs in short supply, especially for automotive needs with the increase in the manufacture of EVs and hybrids, but substrates are needed for their mounting and connection to the outside world. As a result, major automotive companies in Japan, the US, and Europe have curtailed production in several factories to the tune of several million vehicles in the coming year.

Automating paste application saves time and money.

Increasing productivity through process automation, software intelligence and multitasking capability are the foundation of Industry 4.0. Executing manufacturing tasks with exponentially more efficiency and precision ultimately drives cost lower and quality higher. This is proven across operations within numerous industries. As one of the critical sub-processes in SMT manufacturing, stencil printing is an area where substantive gains in quality and cost-efficiency can be made. Often overlooked is the smart factory approach to solder paste replenishment, though it is integral to a true closed-loop system.

Obviously, in order to print, material must be on the stencil in front of the blade. Currently, the predominant method for achieving this condition is manual application. A line operator physically scoops paste out of the jar and places material on the stencil. This seems like an appropriate use of operator resources, as they are positioned on the line anyway, but, in the “little and often” methodology for screen printing processing, this approach is counter to process stability, optimized throughput and cost-efficiency. Manual application of paste could be carried out more frequently to comply with “little and often,” although that would require a machine stop, which may impact throughput and, therefore, cost. Conversely, the operator can apply a large volume of paste on the stencil to accommodate more prints, which may alleviate some of the throughput concern, but could have an adverse effect on process stability.

To continue reading, please log in or register using the link in the upper right corner of the page.

X-ray can’t catch all failures.

This month we we look at solder joint separation from pads with dye and pry testing, which is of course intended, and in FIGURE 1 shown as a perfectly good solder joint. (Well, until I covered it with dye and broke it, that is.)

To continue reading, please log in or register using the link in the upper right corner of the page.

Press Releases

- SMarTsol America Expands Partnership with ASMPT and Strengthens Regional Coverage in the United States

- Absolute EMS Appoints Mark Sika as President to Lead Next Phase of Growth

- Beyond Torque: New Seika Machinery Webinar Reveals How Strain Gage Technology Exposes Hidden Bolt Axial Force Risks in Battery and PCB Assemblies

- New SASinno Ultra-i1 Gives K&F Electronics Added Flexibility in Selective Soldering