The world over, countries are adopting the core elements of REACH, Europe’s three-year-old regulation on chemical use.

As the EC’s Environment Commission states, REACH aims to improve the protection of human health and the environment through the better and earlier identification of the intrinsic properties of chemical substances (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/reach/reach_intro.htm). But what it says next is equally important: “At the same time, innovative capability and competitiveness of the EU chemicals industry should be enhanced” [italics mine].

Indeed, what REACH and its relatives around the world will necessarily create is such a bewildering maze of paperwork and fine print that they will act as de facto trade barriers. As Greg Dripps, Dow Electronic Materials’ global manager, Product Safety & Stewardship, noted recently, “Entry to markets will be slower.”

Speaking at the IPC Symposium on Electronics and the Environment in mid July, Dripps pegged the shifting worldview on chemical safety to the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, at which the concept of the precautionary principle was introduced. There, it was agreed to aim, by 2020, to use and produce chemicals in ways that minimize significant adverse effects on human health and the environment.

Certainly we’ve had fair warning of what was ahead. Fast forward to today, and the rising tide of substance regulation threatens to engulf us all. To wit:

- South Korea is amending its Toxic Chemical Control Law, and moving toward a list of substances of very high concern (SVHC).

- China is expanding the scope of its REACH-like list, going so far as to apply tests to chemicals under R&D – in other words, products for which there may not even be a market. Its scope will include all electronics equipment. However, self-declaration is permitted, and mandatory testing is no longer in effect. Stricter limits are ahead for wastewater and air emissions, although China has traditionally done a poor job of ensuring compliance.

- Taiwan’s new chemical management program goes into effect next year, although some analysts, Dripps included, believe that deadline will slip.

- Malaysia’s proposed laws closely resemble REACH, but implementation is being delayed.

- Japan’s CSCL is migrating toward REACH, with phase-ins coming this year and next. Japan will ban some plating bath additives such as chromate and permanganate.

- Canada’s “short list” has 4,300 substances on it, of which 500 are deemed “high priority.” Celestica supply chain management engineering consultant Kevin Weston says to plan on a 10-month lag for the government to respond to the submittal of chemical information.

- In the US, laws vary by state. Nationally, the toothless 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act gives the Environmental Protection Agency authority to regulate and test chemicals that pose a health risk – but only for certain industries, and only when there is evidence of harm. In practice, just five chemicals have been restricted. It’s so weak, even the American Chemistry Council is lobbying to strengthen it. The new version requires safety determinations of several “expedited action chemicals,” including lead and Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA), the flame retardant used in most laminate.

This, of course, means millions of chemicals and mixtures. My own SVHC (shortlist of very high concerns) is just how, exactly, we are going to collect and register all these data. Just knowing which companies are obligated to report information is a nightmare. (Hint: It’s not just the original chemical manufacturers. In fact, in some cases, distributors could be on the hook.) According to Kathleen Roberts, executive director of the North American Metals Council, under the Inventory Update Rule, there’s a reporting deadline of Sept. 30, 2011, for any chemical used this year. (Forms may be downloaded from the EPA website.)

The fundamental shift is not just the extent of substances to track. Rather, it’s the philosophical change that chemicals are guilty until proven innocent. Given the enormous difficulty chemical engineers have in separating the effects of one substance from others in its working environment, I can’t imagine how this will be accomplished.

Individual companies already are feeling pressure from down the supply chain. In researching solutions, I came across Actio (actio.net), a New Hampshire-based company that has developed sophisticated software for organizing and managing material safety data sheets, and cross-checking them against the latest global regulations. Jabil, for one, is now rolling out some of the Actio modules across its entire enterprise.

It couldn’t come at a better time. One major materials supplier to bare board fabricators told me he receives at least one request a day, often from customers in China, to cross-check their products against a regulated substances list. The checklists can contain up to 2,500 chemicals. Oh, and by the way, the company does not maintain an electronics database; it keeps a binder. (This is probably what Dripps had in mind when he noted the market barrier.) It’s enough to send employees jumping off every workplace roof, not just Foxconn’s.

There’s a silver lining. If they try, it will solve the US unemployment issue.

Mike Buetow is editor-in-chief of CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY; mbuetow@upmediagroup.com.

Be aware that heavy parts are prone to falling off during soldering.

As automation becomes more prevalent and sophisticated in electronics manufacturing, plated through-hole designs are being phased out. PTH requires manual assembly labor that is less cost-effective than automated SMT methods, and is not feasible when dealing with ultra fine-pitch devices. That said, many designs still mix PTH and SMT. PTH also remains in use for some heavy power connectors, transformers, and other devices where strong mechanical bonds are required.

Here we outline key best practices for double-sided, mixed-technology design.

K.I.S.S. Keep it SMT simple! On double-sided mixed boards, the solder side should be kept simple, meaning:

- Discrete components wherever possible.

- No fine-pitch devices or ball grid arrays.

- Component height not more than 6 mm.

Manufacturing problems arise when components on the solder side of a mixed board are too heavy. If the board is assembled using a solder reflow pass for each side, heavy SMT parts attached to the solder side during the first pass may fall off during the second pass.

The general rule of thumb is, if the component is more massive than a PLCC-44, it will not hang on by surface tension. Said more technically, the mass to solder pad surface area ratio for such devices should be lower than 4.5 gm/cm2.

The solder side of a double-sided mixed-tech board may also be soldered by wave solder if the design permits. Using only discrete devices on the solder side and avoiding BGAs and fine pitch components keeps this option open. Solder joint formation using wave solder techniques is much more likely with these types of devices.

“Submarining” is a term used to describe the difficulties encountered when the leading edge of a board passes under the top of the wave on the wave machine. Solder will run down the top side of the card and essentially render it scrap. Very large panels with improper support are prone to sag in the wave solder preheat and any previous reflow cycles. This can increase the chances of a submarine.

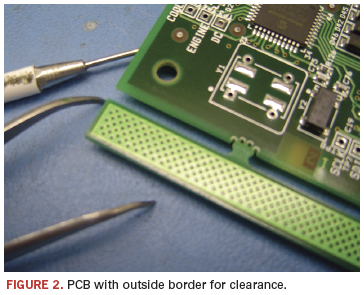

Keeping a clear space around the edges of the board permits use of snap-on titanium stiffeners. These increase the rigidity of the panel and help prevent such occurrences.

Snap it. Another manufacturing design technique to observe is use of snap-off materials on the edges of the board. As mentioned, titanium stiffeners can then be used to help make the board more rigid. It also permits the panel to be handled smoothly in conveying and clamping systems. A 0.200" clearance is adequate, but nothing (not even fiducial keepout areas) should be placed in this zone.

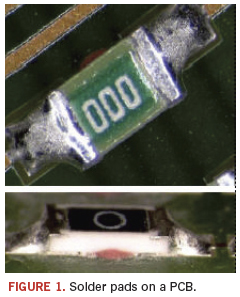

Pad it. Pad dimensions should be carefully considered on the bottom-side SMT of a double-sided mixed board. This includes extra thieving pads for wave-soldered ICs and extended toe pads to facilitate solder wicking. Both can significantly improve the yield at wave soldering (Figure 1).

In addition, components on the board should be oriented so that the solder joints are not shadowed as the board moves through the wave solder.

Clear it. If a double-sided mixed board is so dense that the above guidelines cannot be observed, a special fixture called a selective wave fixture (also known as a pallet) into which the board is snapped can be used. This masks the bottom-side surface mount from exposure to the wave. To do this, there must be sufficient clearance (0.1") between the PTH and SMT lands on the solder side so that the SMT can be masked by the fixture (Figure 2).

Keep in mind that fixtures add cost to the product; several fixtures are required, at several hundreds of dollars per fixture, and they have to be cleaned, loaded, unloaded and occasionally replaced.

Think single-sided. Overall, when designing a mixed board (using SMT and PTH), it pays to think single-sided! If possible, PTH parts should be placed on the same side of the board as the primary SMT devices. Double-sided PTH or PTH on the wrong side is almost certain to require manual soldering. There is just no other way to process them cost-effectively with existing automation.

George Henning is vice president of manufacturing at OCM Manufacturing (ocmmanufacturing.com); george.henning@ocmmanufacturing.com.

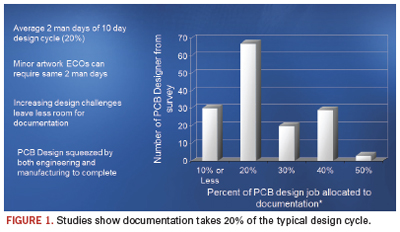

Dedicated tools help reduce the once-manual job by 20% of the typical design cycle time.

The question posted to the DesignerCouncil email forum was simple and straightforward: “Why on earth can’t these companies make a product out of the box that does engineering documentation well? I find it hard to believe there can’t be a boilerplate level delivered that could handle 80 to 90% of most companies’ documentation needs out of the box. … Even the BoM reports delivered out of the box from Oracle are absolutely useless. You need an integration company or an internal team of Oracle experts to spend a fair amount of effort just to get a usable BoM report.”

What’s fascinating, if not somewhat predictable, is how many firms take software that is intended (and good) at one function and repurpose it for something else. Take, for example, two of the best-known product life management tools: Oracle’s PLM and PTC’s Windchill. Good programs, both, but they were never intended to handle circuit board documentation. It’s one reason why it takes, on average, two man-days of the typical 10-day design cycle to complete the documentation (Figure 1).

Best-in-class processes reduce the amount of time spent creating the documentation; are automated so as to create a “living” document, or one that’s not fixed in time, unlike a paper printout of a pdf where, in the event of an engineering change order, the documentation needs to be regenerated; and facilitates product flow to the extent that the end-product quality is enhanced. As Downstream Technologies cofounder Joe Clark says, “Documentation is much bigger than just design, fab and assembly.”

Designers are pros at stretching the limits of CAD tools and other software, but at some point the deficiencies become too glaring to tolerate.

It’s why I’m surprised more haven’t turned to BluePrint, which purports to solve the headaches by providing access to all the electrical intelligence contained in the PCB CAD database to create detailed documentation in reportedly a far shorter timeframe than using traditional ECAD or MCAD tools.

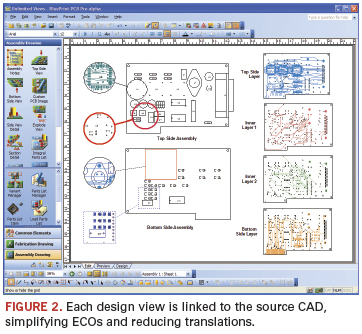

The brainchild of DownStream, BluePrint was developed by former board designers who understand from firsthand experience the pains of their ex-colleagues. It uses a drawing- and sheet-based approach to create actual PCB documents (drill drawing, assembly drawing, parts list, and so on), and stores them in a digital release file. BluePrint uses the CAD data to automatically create unlimited views, details, and charts of the PCB, and can revise the documentation to reflect new PCB changes, reportedly in seconds. It’s not just a tool change; it’s a change in methodology.

Like MCAD, BluePrint can document drafting and dimensional specifications. Where BluePrint separates itself from the traditional MCAD tools, however, is in the

number of required translations. Mechanical tools aren’t designed for the specific nature of a printed circuit board. To wit: MCAD cannot distinguish between a layer on a circuit board and a floor of a building. Meanwhile, BluePrint is a full 2-D drafting tool designed specifically to create PCB documentation and capable of creating anything that the CAD, fabrication and assembly departments might need. It eliminates constraints imposed by the PCB design tool for documentation, but retains the intelligence lost when using an MCAD tool for documentation.

The best example of this is BluePrint’s support of unlimited PCB design views on any drawing sheet. Each instance of the design can be set with different display settings, scaling and formatting. However, each is also linked to the source CAD to automate ECOs, requiring one file translation from the source PCB CAD data to BluePrint (Figure 2).

As our emailer suggested, most users try to generate documentation from their ECAD tool. But ECAD was never intended for that purpose: Dimensioning is the domain of mechanical design. In practice, it’s another story. Asserts Clark, “Users do [documentation] in ECAD because they need to get it onto the piece of paper. There are lots of things done in the electrical design process that have nothing to do with electrical design; it’s all aimed at the documentation.” For instance, the use of assembly variants or mechanical components, which are never simulated but are pushed into a design capture or PCB layout tool to ensure they are represented in the final bill of materials.

BluePrint was developed to work with existing EDA tools. The MS Office environment requires a single load of the entire PCB CAD database to start the documentation process, and uses all the CAD intelligence to help create the documentation. ECOs are added by “refreshing” the source CAD data. BluePrint refreshes the documentation package, adding the new data in every instance of a board view, detail and chart.

“BluePrint brings ECAD design into the documentation tool,” says Clark. There, in the gallery (also known as the library, the term “gallery” is used so as not to be confused with the data for the PCB packages and land patterns), users create a drawing sheet, dragging and dropping the elements onto it. Any element – the number of zones, the font, colors, format, and so on – that is dragged and dropped on a sheet is “intelligent”; links remain active from the underlying design database, so if the links change, everything within the drawing is updated.

Inside the file are contained via stackup and drill layer pairs; drill symbols, patterns and charts; notes and callouts; mechanical component support; parts lists and assembly drawings; tooling, and so on. Schematic, Gerber, DFX, PDFs, plus any graphic or audio files are all stored. Or, in the words of Rick Almeida, DownStream’s cofounder, president and a former designer, “Any data used to create documentation and drive manufacturing.”

Automation of documentation is created by first creating the graphical “pictorial” of how the user wants to see a specific documentation element, for example, a “Via Stack-Up.” The graphical instruction defines how the via stackup should look. The via stackup could be amended, and the template modified to company-specific versions and saved for reuse. The template graphics are linked to data fields that pull the correct information from the PCB CAD data to intelligently create a via stackup that reflects the design intent and remains linked to the CAD data, so when the CAD data are updated (e.g., new layers or via ranges added or deleted) the detail is also automatically updated. “Essentially we use the same approach that is found in MS Excel chart build, where empirical data are married to user-specific graphics,” says Almeida. This same process goes for drill charts, parts lists, finger chamfers, coordinate lists, exploded views, etc.

BluePrint supports automation of the assembly drawing as well. This includes parts lists, which, even if not shown in the documentation set, are in the underlying design database and can be referenced as needed. The search function can find specific parts and component outlines. What it is not is a bill of materials management tool. “The parts list is a key part of the documentation,” explains Clark. “Documentation affects the parts lists, because as designers do the layout, they add mechanical parts, such as face plates, screws, washers. They need to be able to add to the parts lists and export them to the right department so they can add to the BoM and bring in all the attributes of the parts.” With BluePrint, users can import an external parts list from PLM or other enterprise systems, and sync the parts list with the assembly document, then export the parts list back to the enterprise system for ongoing management.

BluePrint follows the orientation of the board to place component reference designators. (The latter can be hyperlinked, too.) Assembly variants can be created at both the parts list level and also with a graphical assembly pictorial, with special legends to show what’s been installed, uninstalled or substituted. Documents such as relevant standards can be inserted as hyperlinks into the database. It also can generate rework sheets, showing cuts and jumpers, and include installation procedures.

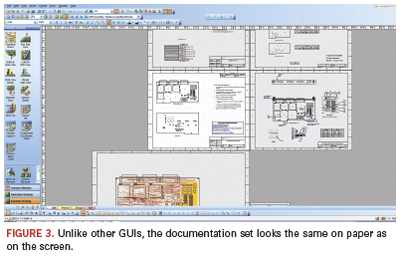

One complaint about reference designators in Oracle and SAP is that they do not display all instances of a particular part number with the part number and description in a single screen or menu. That’s not an issue for BluePrint. The documentation set in the GUI looks just as it will print on paper (Figure 3). The documentation package also can be exported as a pdf and posted to the Web, or as html on a company Intranet.

“It treats the end-product like a PCB, not a generic widget,” Clark says. “We don’t know how good our documentation is until we print it. Then, if something is wrong, we need to go back upstream and fix the ECAD database, then print again. What we do is allow the user to work with the documentation as it will be delivered upon release. This is a full 2-D drafting tool; it’s not intended to replace the mechanical group, but you need to be able to move and place things when doing the documentation. The handcuffs need to be removed.”

As we reported several months ago, Qualcomm has become one of the largest companies yet to standardize on BluePrint. Come this time next year, I would expect many more such announcements – and far fewer plaintive missives like the one at the beginning of this story.

Mike Buetow is editor in chief of PCD&F/CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY; mbuetow@upmediagroup.com.

As with SMT, expect consolidation, especially in China.

For those of us who came to the solar industry from electronics, it is hard not to draw comparisons between their respective trade shows. Especially as this year, the world’s top solar shows are as big as some of the leading electronics shows, filling numerous halls in some very big venues. I should point out that last year, I would not have thought of comparing the two sectors’ events. The year before that, many solar shows were almost insignificant; three years ago, a solar event would typically have filled a single hall in an average exhibition center. Visiting Taiwan two years ago, I walked an entire exhibition in 15 minutes. But that’s all changing, and rapidly. In fact, the speed at which these events are growing is like nothing else we’ve ever seen, and that holds true wherever you are in the world.

By dint of the fact that Germany is still the largest and best established photovoltaic marketplace, Europe still hosts the world’s largest events, such as the big shows in Germany, and the annual EUPVSEC, held in Valencia on alternate years. Some major shows in the US, particularly on the West Coast, are also growing quickly.

And as China grows exponentially as a solar market, Shanghai, too, with its proximity to the main solar manufacturing areas, and for its excellent access, is proving to be a massive and fast-growing success. That said, it is, like all the Asian events, smaller than its European counterparts, presumably because there are so very many to choose from. If you were so inclined, you could visit a different solar show in China almost every week.

That the solar industry is global can be seen from the fact that wherever you go – Europe, Asia, the US – the shows are all pretty much the same, apart from their size. And it's striking that they are so all-encompassing. Everybody’s there, from the companies making the big smelting furnaces that melt silicon and grow it into ingots, through cell manufacturing equipment people like us, the panel manufacturing and assembly equipment suppliers, the firms that make the fixtures that you bolt to your roof to house the panels, the panel installation equipment suppliers themselves, right through to the guys who provide the ladders and cherry-pickers for getting the whole shooting match up onto your roof.

And that’s before you go to the non-PV-specific shows. The events promoting solar in general add in the dimension of thermal solar and all the equipment, consumables and issues involved in this part of the solar energy marketplace. From sand to water to sunshine – a vertical, horizontal, highly diversified marketplace.

This must be because solar is relatively new. Clearly, the challenge for any new show is to fill the halls and raise the exhibitor and visitor numbers. As the event grows, however, it will get to a point where its large size can be a disadvantage. Consider only that the visitors who want to discuss cell manufacturing equipment with us are extremely unlikely to be the potential future clients of the rooftop installation equipment guys down the aisle in booth B4. That’s OK in a smaller show, but in a larger exhibition, even if well organized into distinct sectors, high diversity can become dissipative, and for the visitor, extremely bewildering. There must be a point at which it makes more sense to divide a large event into smaller, dedicated exhibitions – which will arguably have more vigor, thanks to their new focus, permitting them to grow into their own specific potential.

This is exactly what happened in the electronics sector, with shows like Electronica, now in its 24th edition. Based in Munich, this now biennial show, spanning a broad spectrum from electronics manufacture to electronics products and applications, grew swiftly, to the point that after just five editions, the decision was made to split the electronics production sector into its own dedicated show, Productronica, leaving Electronica with a specific focus on components, systems and applications. They now share the same venue, taking place on alternating years, and have both grown immensely since those early days – testament to the vision and courage of their organizers. Many electronics events followed similar evolutionary paths as they grew – and outgrew – their remits. Others merged, as a natural consequence of there being too many shows for exhibitors and visitors to support.

In the near future, it is likely we will see the same thing happening in the solar show circuit. The larger shows will divide into more targeted events, while the smaller shows, especially in China, where there are simply too many to visit, will probably merge or disappear. As industry growth settles and exhibitors define advertising budgets accordingly, it is likely that in a few years’ time, there will be a handful of big shows worldwide. These will be chosen by participants for their focus, capability, and it has to be said, for their costs, which, compared with similar electronics events, are currently very high. They will foreseeably form the solar industry’s base, as launch venues for the latest and greatest in solar, attracting global interest from exhibitors and visitors alike. And, like their counterparts in today’s electronics sector, they are likely to be supported by various orders of smaller events that invite participation through their specific technology, market and regional focus. For us at DEK, who have seen it happen elsewhere, and who believe absolutely in supporting our industry well, this is a scenario that makes a great deal of sense.

Andy Ure is business development director, Americas at DEK Solar (dek.com); aure@dek.com.

Breaking down cleaning processes into basic building blocks reveals the optimal choice.

Post-reflow residues of SnPb and newer Pb-free soldering materials are more difficult to remove due to increases in component density, larger component packages, higher lead counts, finer lead spacing and lower stand off distances. While modern aqueous alkaline cleaning agents effectively remove these flux residues, achieving satisfactory cleanliness depends on the interplay of temperature, exposure time, chemical concentration and mechanical energy. At first glance, the path toward a perfect cleaning process may appear elusive and complex, if the process with all the associated variables is considered. As a chemist, I would equate the challenge of setting up a proper cleaning process to that of synthesizing a complex molecule. In fact, one approach to organic synthesis known as retrosynthetic analysis, or “the disconnection approach,” is also useful as a strategy for selecting the perfect cleaning process.

A disconnection approach is simply a way of breaking down a very complex target to make the best path to success more apparent. With this approach, a chemist will start with the structure of their target molecule and progressively go through the mental exercise of cutting bonds to create simpler molecules. The result is the complex molecule is reduced to individual building blocks where each can be judged as a viable or non-viable option by asking common sense questions: Is the building block readily available? Is it expensive? Is it safe to use? Once a viable list of building blocks is obtained, simply reversing this process gives a synthetic route to the desired target molecule from simpler and commercially available starting materials.

What does this have to do with selecting a cleaning process? More than you think. Like a chemist who faces the task of synthesizing a complex molecule, engineers developing a cost-effective, long-term cleaning process often feel overwhelmed. Naturally, they rely heavily on equipment and chemistry vendors to offer advice and support. Yet unless the customer fully understands the building blocks that make up the total cleaning process, as well as how each one can impact the process window, the result may be far from optimal, and expensive.

Before beginning any evaluation, it is important to have well-defined requirements or a “wish list” of what you would like to achieve. In other words, there are many factors to consider and rank, such as material compatibility, cost, consumption, throughput, etc. Some customers may need high belt speeds to handle high volumes of parts, thus avoiding bottlenecks in production. Others may place more value on low operating temperatures, which save energy and reduce evaporative losses, etc. The cleaning chemistry and cleaning equipment have to be considered in parallel, not selected sequentially. For example, selecting a cleaning chemistry that is not appropriate for use with high-pressure sprays can result in a shop full of bubbles.

Using a disconnection approach, one can break down cleaning processes into basic building blocks so that each can be tested against customer requirements. Basically, cleaning involves chemistry (or water), force, temperature and time, and each of these variables influences cleaning performance or material compatibility. Consequently, it is important to design your evaluation in such a way to optimize these factors to achieve your predefined goal. Communicate your objectives with each supplier openly and in advance so that they can share with you how they can contribute. For example, if your primary goal is to achieve the fastest belt speed, this will require achieving the desired cleaning results within short periods of exposure time. In the case of spray-in-air processes, contamination is partially dissolved or emulsified by the cleaning agent and partially washed away by the kinetic energy of the spray jet. Since chemical energy provided by the cleaning agent and the mechanical energy of the equipment will have significant impact on exposure time, it is important to design your experiments to test each factor independently.

The key factor for long-term success is to never recombine the building blocks during the evaluation until the impact of each important factor has been truly differentiated. For example, one should never allow vendors to change nozzles while doing a chemistry evaluation. Any change in nozzles would result in significant changes in mechanical energy, which will overshadow or negate otherwise significant differences in chemistry. One chemistry can be made to outperform another this way. Once the best chemistry is selected by keeping all parameters constant, explore improvements in mechanical energy until the best equipment is selected, etc. The same can be said of changing chemistry while testing different equipment configurations. This seems logical, but you would be surprised how often these mistakes occur.

In summary, you do not have to be an expert in solvency or in equipment design. However, you do need to understand the cleanliness and surface quality requirements of your own product line in the context of your process. You should also disconnect the process to take a good look at the impact of each building block. It is unwise to simply adopt a suggested strategy without question. Make sure the cleaning chemistry is truly optimal for your process. Likewise, independently confirm that the cleaning equipment is best suited to your product line.

Harald Wack, Ph.D., is president of Zestron (zestron.com); h.wack@zestronusa.com.

Finer powders may be more prone to solder balling.

This month we feature one recent problem of solder balls or fines.

Dip solder paste now commonly used in package-on-package (PoP) assembly has a lower metal content, more often designed for nitrogen reflow than air, and also has smaller solder particle size. The powder may be Type 5-6, as opposed to a stencil printing grade of Type 3-4, and hence more prone to solder balling during reflow. It is fairly uncommon for standard SMT solder paste to slump and solder ball like the example, unless it has been poorly stored.

It’s important for engineers to learn how to conduct solder balling and solder slump measurements of paste from different vendors. IPC and SMART Group specifications describe tests of this type using automated test equipment available from a range of suppliers. In simple terms, a sample of paste is printed on a non-solderable surface – in this case, a ceramic tile – and reflowed. The result observed should be a lack of spread during preheat, one single ball on the surface of the plate after reflow.

These are typical defects shown in the National Physical Laboratory’s interactive assembly and soldering defects database. The database (http://defectsdatabase.npl.co.uk), available to all this publication’s readers, allows engineers to search and view countless defects and solutions, or to submit defects online.

Dr. Davide Di Maio is with the National Physical Laboratory Industry and Innovation division (npl.co.uk); defectsdatabase@npl.co.uk. His column appears monthly.