The brains behind the former Orbotech AOI group are ready to forge their own path.

With its acquisition last April of Orbotech’s AOI assembly business in the US and Europe, Germany-based distributor Prodelec launched a new company, Orpro Vision (orprovision.com), and overnight became the proud owner of one of the larger installed bases in the world, many at high-volume automotive parts manufacturers like Delphi. And the potential for growth remains: Orbotech reported sales of equipment related to assembled PCBs of $22.1 million in 2008 and $28.3 million in 2007.

With the accounts came certain R&D staff as well, which, combined with new recruits, bring the total staff to about 25 overall, about one-third in development, the rest in support. Production remains in Israel, where machines are built by a third-party. The company has platforms for SPI and AOI, and introduced a prototype of a benchtop AOI during Productronica.

President Arnon Tuval, Massimo Gatti and R&D manager Adam Shaw spoke with editor-in-chief Mike Buetow in November. Excerpts:

CA: Has Orpro Vision retained much of Orbotech’s footprint?

AT: I came to Orpro Vision from Orbotech, where I was vice president of sales. I was based at Orbotech’s American headquarters in Billerica, MA [Ed: suburban Boston]. Orpro Vision’s Americas headquarters will also be in Billerica. We have our demonstration site, training and support there. The global headquarters is in Hameln, Germany.

CA: How does a company make the jump from distribution to conceptualizing and building product?

AS: When we acquired the business, the research and development of Orbotech’s assembly group came to Orpro Vision. The core of the team was there. We brought three R&D engineers from Orbotech. Then we recruited their colleagues, bringing the staff to 19. They are very experienced. So unlike a traditional startup, today we not only know what to do, we know what not to do.

We also have one of the largest installed bases for inspection machines. We have more than 1,000 machines in Europe, more than 1,000 in Asia, and 450 in the US.

CA: Has the economy affected Orpro Vision’s launch as an OEM?

AT: Because of the economy, we didn’t miss a lot because most companies weren’t in buying mode.

CA: What can you say about your finances?

MG: Orpro Vision is a subsidiary of Fin.Pro, the Italian holding company. Fin.Pro has been a business partner of Orbotech for several years. Fin.Pro is totally private. We needed no outside banks to make this deal.

CA: Have you retained any of the Orbotech distribution channel?

AT: We are in discussions at present. We will have some new distributors in Europe and the Americas.

CA: How are you positioning Orpro Vision? As a technology leader, or a fast follower?

AS: We are very much into innovating. We debuted a benchtop system at Productronica. This new system was developed in five months. It is a totally new image acquisition platform. The official release will be in 2010.

MG: In one way, we are starting from scratch. But we have 15 to 16 years’ experience in AOI. We want to deliver very scalable solutions to the market. We know the engine and optics must be top quality.

AT: We want to be innovators and market leaders, but we want to stay close to the market demands. That’s why we are introducing a benchtop system. CA

Switching from a single offering to end-to-end involves breaking down certain internal barriers.

Everyone knows it’s an outsourced world. So how to compete? How about integrating vertically?

Good reasons abound, but first and foremost, integrating is a response to existing customers’ needs. The vertically integrated supplier transcends the mundane to become a key factor in its customers’ success. Generally, too, it appeals to a broader base of prospective customers, allows outsourcing trends to be fully exploited, creates revenue and margin opportunities, and changes the scope of competition.

Formed in November 2002, upon its divestiture from IBM’s Microelectronics Division, Endicott Interconnect offers end-to-end electronics packaging and production, from semiconductor package design and fabrication, to laminate development, bare board fabrication, component assembly, test, and box-build. It takes a lot of space and a lot of manpower to do all this well (in our case, 1.4 million sq. ft. and more than 1,600 employees), and we’ve enjoyed a good run after a challenging start as a brand new company.

Now our model evolves. Through the IBM years, we were a manufacturer of components and an integrator of systems in the form of capital equipment. Newly formed EI focused strictly on manufacturing components. Today, we manufacture components while simultaneously growing a systems integration business in which we move backward toward the bare die and forward toward direct fulfillment.

Along the way, we’ve learned that the more you offer, the more credentials are necessary. (In our case, the list includes AS9100, NADCAP, ISO 13485, ITAR, among others.) We recognized the need to spend money on people, equipment, facilities, and capabilities (capital spending hovers around 8% of annual revenue, and our R&D budget ranges from 2.5 – 4.5%). We learned to build incrementally on existing talents. And we aggressively sought ways to do more for every customer.

To extend our reach first meant recognizing the limitations of our structure. Silo organizations were built around business units (component substrates, printed circuits, printed circuit assemblies), with conflicting objectives among units. When it came to competing for resources, a certain selfishness prevailed.

To tackle the problem, we unified the business units under a single management team and hired staff with skill sets the organization lacked. This also meant shedding workers who would not, or could not, support the changes that had to be made.

Concurrently, we remodeled existing space to establish premier manufacturing facilities. We allocated capital to increase capacity and improve capabilities, specifically focusing on capabilities that would enhance the vertical integration strategy. For instance, we acquired eV Products (now eV Microelectronics). The CZT crystal technology we gained with the acquisition is used in sensing applications in medical and homeland security applications – two market segments that are integral to our strategy. We added staff with program management skills. And we sought synergies with public and private sector organizations to leverage resources, exemplified by the Center for Advanced Microelectronics Manufacturing on our campus.

‘Brainpower as a differentiator.’ Besides bringing in talent to plug identified gaps, we also redoubled our efforts to use existing in-house expertise. We had an R&D group with over 800 career patents. We began to focus its efforts on customer problems – whether materials, processes, or systems. Sometimes we ended up developing new processes and materials where commercially available ones were inadequate. In short, we profited by putting our technical experts face-to-face with our customers. Where some companies tout their pricing or global reach, we used brainpower as a differentiator.

Meanwhile, we set about penetrating the customer on every level. Within our sales and marketing organization, we built skill sets compatible with selling broader capability. The vertically integrated company sells more than a single widget or service, so it must look deeper and wider at what the customer is doing and what they need. Ask: What more can I do for you? How can I show you? Then blow your own horn, often and loudly (this column is one example).

It takes bench strength to win big end-to-end programs. We hired electrical designers and software engineers, added system architecture expertise, applied our expertise in hardware design (substrates, power, cooling), and figured out how to cost and price all these new things. Through it all, we learned to collaborate both more often and to a greater degree with customers and other organizations.

Moving from a single product or service to a vertically integrated model requires constant focus on how to make your company more attractive to existing and prospective customers. At the same time, however, it means keeping an eye on the ground to avoid pitfalls that come with doing multiple new things simultaneously.

Make use of the underutilized talents of your staff, and plan on hiring and firing, too. The transition requires collaborations, partnerships, and, yes, spending, but the payoffs can be huge. CA

Rex Green is global sales manager and product manager at Endicott Interconnect Technologies (eitny.com); rex.green@eitny.com.

At the risk of beating the tin drum (and wasn’t that movie painful enough to sit through?) once too often, I will mine (get it?) the Conflict Metals subject one last time.

To recap, Conflict Metals refer to ores extracted from the battle-raged Democratic Republic of Congo, where millions of citizens have died, casualties of a fierce civil war underwritten in part by revenues from contested mining activities.

Following my last two columns, I have heard from various sources who hoped to refine my thinking. One noted that the Congo supplies less than 5% of the world’s tin, suggesting the electronics industry, which as these things go is hardly a major consumer of the metal (some estimates put electronics’ share at 2% of the global consumption), could survive just fine without the DRC as a source. (By the way, tin owns no patent on the issue. The DRC also sits on large deposits of tantalum.)

Second, while the audits proposed by the International Tin Research Institute and other similar-thinking groups (see last month’s Caveat Lector) are a step in the right direction, in some cases they are redundant with existing corporate practice. And reclaimed materials are exempt from the discussion, because, among other reasons, the alternative would be to landfill the disputed metal. As Cookson Electronics president Steve Corbett, one of the few willing to speak on the record, told me, “Customers are not looking for verification on reclaimed materials. And we say, ‘You really don’t want to throw a wet blanket on reclaim, because you want to keep it out of landfills.’ ”

In that sense, even the most intense certification programs are inherently incomplete. While some companies would be able to guarantee there are, in the words of one colorful source, “no Congolese atoms” in their products, there simply is no way for industry as a whole to ensure its products contain no amount of Conflict Metals.

In the US and elsewhere, pending legislation – which one source called “ludicrous” – emits the radioactive notion that through industry pressure, governments can solve the civil war. “According to the politicians, there are legitimate mines,” said one solder supplier. “It’s like the cotton picking of the Civil War: the South cotton is bad; the North is OK. We’re picking sides in a civil war in Africa.”

Nevertheless, it would be a mischaracterization to suggest solder vendors are simply throwing up their hands in despair. Solder suppliers are actively trying to determine if their smelters use ores from the DRC and, if so, remove scofflaws from their vendor lists.

It’s true the industry cannot determine which tin atoms came from where. Still, pressure is heavy from OEMs like Nokia, H-P and Intel that wear their respective corporate social responsibility (CSR) statements like a badge. That could explain why solder suppliers aren’t balking at ITRI’s proposal to add $50 a tonne to underwrite compliance audits, as they seem intent on passing those costs along to customers that demand the audits.

But I came away certain that the industry should push back on this issue. This approach should be twofold: First, it should use governmental channels. Though IPC might be too small to be effective, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) or the National Association of Surface Finishers (NASF) might be a good place to start. (If you can put a good spin on hexavalent chromium, what can’t you do?) Second, it needs to attack the exchanges.

According to my sources, the London Metal Exchange will not certify that the metals in its warehouses are free of Conflict Metals. Solder vendors should collaborate to remedy this, for if the LME doesn’t comply, the effort toward compliance will be uncertain, at best.

Finally, I should clarify that not every solder supplier buys raw materials from the exchanges. Some buy direct from smelters. My apologies for suggesting otherwise.

Jumping, but not for joy. I’m old enough to remember the old Toyota commercials where everybody would jump into the air at the end, and the voiceover would say, “Oh, what a feeling!” Well, Toyota has made car owners jumpy again, but not with pleasure. As I write, the nation’s media and blogosphere is afire with speculation over what is to blame for the automaker’s sudden acceleration problems. Some, including Dr. Michael Pecht of University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Life Cycle Engineering (CALCE), are pointing to a breakdown in the electronics throttle system. Which begs the question, are the much-publicized recalls tied to a lead-free problem?

Bob Landman, a reliability expert and a Life Senior Member of IEEE, has been vocal that the connection between lead-free solder and tin whiskers is both real and potentially deadly. He asserts “the increased use of electronics in automobiles when mixed with RoHS can make for a deadly cocktail. We don’t know what the causative agent [in regard to the Toyota recalls] was, but I have heard recently of new autos showing up at dealers that will not start. That cause has been linked to tin whiskers.”

We do not yet have enough information to determine whether tin whiskers or even lead-free solders are at issue here. One would hope Toyota comes clean, if indeed the true cause can be determined, so that the industry at large can learn from their mistakes.

P.S. Landman moderated a chat on tin whiskers during Virtual PCB this month. See the transcript on-demand at www.virtual-pcb.com.

There is a practical way to sequentially implement the two efficiency systems.

There is no debate that correctly applied Lean manufacturing philosophies can increase production efficiency. However, there are variations in Lean tools. The fundamental difference between Lean and Lean Sigma is that while Lean manufacturing focuses on the elimination of waste by removing steps in processes, Six Sigma fine-tunes processes by focusing on specific process improvement activities.

Implement core Lean philosophy first. EPIC chose to implement Lean manufacturing principles first. Major points of focus included:

Process flexibility. A critical first step was developing a production process that could handle small lot sizes over a wide range of customers and product types. This included working with suppliers capable of modifying their equipment to support rapid changeovers.

Operator cross-training. Operators are cross-trained in several production processes and certified to a range of skills in a training matrix. Compensation is tied to certification levels achieved. A core group of operators is deployed in a range of critical production processes and moved throughout the factory based on areas of highest demand.

Visible/frequent communication. Visible scheduling tools are used to ensure that scheduling data are in the hands of those charged with producing products. EPIC uses a three-zone system for production staging and a two-bin system for material planning. There are no production schedulers. Operators are empowered to prioritize the production sequences for each line based on color-coded pull signals. Material use is coordinated electronically between facilities via a bar-coded “virtual” Kanban planning system that mirrors the “visual” card system on the factory floor.

Visible metrics. A Plant Operating Review (POR) system drives the monitoring of approximately 50 metrics company-wide down to the floor level. These metrics are reviewed on a daily/weekly basis by the customer focus teams, monthly by the plant managers and directors of operations, and quarterly by the senior management team.

Mutually beneficial supplier relationships. We use a combination of supplier education, internal planning tools, excellent communication, and strong working relationships with customers and suppliers to help motivate suppliers to support Lean principles.

Six Sigma as an enhancement tool. Six Sigma principles are incorporated in an enhanced, disciplined analytical approach.

EPIC’s in-house reliability laboratory supported new process definition and validation; new product process validation; and resolved internal, supplier and customer quality issues prior to implementation of Six Sigma tools. Six Sigma’s Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control (DMAIC) approach has now been implemented to enhance design for manufacturing/testability (DfM/DfT) analysis, process improvement and/or corrective action effort.

We have three Black Belts and are in a second wave of Green Belt training. The Six Sigma focus has been on scrap and defect reduction. As focus areas are identified, the appropriate project engineer is given the training, tools and mentoring to analyze the project selected for improvement. These improvement projects use the DMAIC approach.

In the Define phase, participants validate that this is a good project, define the improvement goal and define the team and team leader.

In the Measure phase, the real project work starts. Past performance is measured. Pareto charts and process mapping are utilized to determine the high hitters in terms of defects. The measurement system is validated using a gauge R&R tool, since decisions will be based on the data collected. Typically, an experiment is set up where several people are surveyed using several boards to determine whether an induced defect is the defect that everyone recognizes. This statistical tool measures whether the defect assessment is consistent across people or machines.

The Analyze phase focuses on the critical few areas identified to determine root cause of those defects. A cause-and-effect diagram (also called the fishbone diagram) is used. The team conducts a brainstorming session and then tests its hypothesis. Any variances are analyzed. The team also tries to estimate the impact of an input variable, such as raw material, temperature or line speed, on a machine to the output factor to determine which change has the most impact.

In the Improvement phase, there is evidence of problem root cause. The team develops an action item list to identify what needs to be changed and when it will be changed. The recommendations are then validated.

The Control phase ensures the output continues to be monitored to guarantee the corrective action in input variables stays in place. Any changes are documented. This ensures consistency and documentation of institutional knowledge. Any cost savings is measured.

One recent project involved a goal to reduce scrap from 1.1% to 0.8%. It was determined that the root cause was illumination values that were causing misaligned

placement against the pads on certain BGAs and ICs. To improve the parameters, the team used design of experiments to determine the best illumination parameters by shape of components. It then analyzed manufacturer recommendations and experimented with a range of values to get the best results. Once the results were validated, it made the best combination of values the default in all machines. Because we use a standardized SMT placement platform across the company, this fix has been implemented in all facilities.

The board being analyzed has gone from a 1.1% scrap rate to 0.77%.

Carlos Rodriguez is a Six Sigma Black Belt at EPIC Technologies (www.epitech.com); carlosm.rodriguez@epictech.com.

When halide fluxes lead to corrosion – and what to do about it.

The customer submitted several board assemblies that failed in the field and exhibited corrosion in close proximity to on-board components. The most common source of corrosion on electronics assemblies is residual flux. Fluxes can be highly reactive chemicals that, if left on the assemblies, can lead to corrosion, electrical degradation, and decreased reliability. In the presence of moisture and electrical bias, flux residue can enable dendritic growth as a result of electrochemical migration.

To establish the source of the corrosion, technical data sheets and materials safety data sheets (MSDS) can be used to help evaluate the chemistries of the approved fluxes. The cleaning process also is evaluated to ensure the efficacy of cleaning the fluxes. Further, by establishing a correlation between the composition of the residues and flux chemistries, one can eliminate or confirm the source of the corrosion. Analysis of the residues may be accomplished by employing scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

The introduction of chemistries promoting the advancement of corrosion in electronic assemblies may appear paradoxical. However, the proper flux coupled with effective cleaning processes can negate performance and long-term reliability issues. An abundance of flux types are currently available. J-STD-004B characterizes flux by type: rosin (RO), resin (RE), organic (OR) and inorganic (IN). Flux activity also is designated by the degree of its ionic and corrosive actions. A halide-free flux providing adequate soldering performance with low residue levels may appear ideal. However, flux selection may rely on board type, material compatibility, specifications, component mounting and solderability.

In this case, optical microscopy was used to obtain images of the white (Figure 1) and green residues (Figure 2) observed on the assembly and components. SEM/EDS can provide a qualitative representation of these residues using high magnification microscopy in conjunction with EDS for quantitative purposes. Analysis revealed the white areas of corrosion to be consistent with tin chloride residue (Figure 3) and the green areas to be consistent with copper chloride residue (Figure 4). These residues may form when copper and tin react with chloride ions, which likely came from an aggressive flux that had an extended exposure time on the assembly. Carbon, nitrogen and oxygen also were present in both residues and are typical organic components of the flux. A review of the flux technical data sheets referenced the use of L0 materials. L0 materials are halide-free and were neither the source of the chlorides, nor the cause of the residue. Further review of the materials revealed an aggressive flux also was used in the selective soldering process. The designator ORH1 indicates the highest flux activity level in the OR category and halide concentrations greater than 2%. It is likely this flux is the source of the chlorides and the cause of the residue.

Chloride remaining on the assemblies after exposure to H1 fluxes is common. When combined with moisture and electrical bias, the presence of these chlorides is instrumental in corrosion. An assembly properly cleaned and rinsed after reflow can effectively eliminate the remaining halide fluxes, removing any ionic species necessary for corrosion. Manufacturing processes also must be thoroughly reviewed. This ensures non-approved materials that may lead to reliability issues are not applied.

ACI Technologies Inc. (www.aciusa.org) is a scientific research corporation dedicated to the advancement of electronics manufacturing processes and materials for the Department of Defense and industry. This column appears monthly.

A host of new specifications aims to overcome coverage issues brought on by high-speed circuits.

The influx of high-speed signals on boards, and the challenge to the test environment, has invigorated interest in limited access methodologies such as boundary scan and built-in self-test (BIST). The industry is gearing toward adopting key initiatives to IEEE standards, so as to be able to help resolve these test challenges. The following are the proposals to extend IEEE Standard 1149.1 boundary scan capability into embedded testing, as well as the BIST currently in use by OEMs in the semiconductor and board design areas.

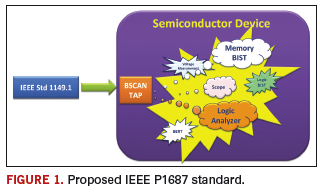

IEEE P1687

The challenge. Board assemblies increasingly are populated with high-speed semiconductors and memory in the GHz range. As a result, placing testpoints on the PCB traces is nearly impossible, as it would degrade signal integrity. Without these testpoints, manufacturers will no longer be able to use ICT to capture defects such as opens, shorts and wrong component values. In turn, this would increase test and overall manufacturing costs.

The proposed solution. OEMs and EMS providers are well aware of these challenges. Their need for a viable solution paved the way for the surge in interest in the IEEE P1687 standard, also known as Instrument JTAG or iJTAG. The objective of iJTAG is to develop a method and rules to access the instrumentation embedded into a semiconductor device without the need to define the instruments or their features using IEEE Standard 1149.1. The proposed standard would include a description language that specifies an interface to help communicate with the internal embedded instrumentation and features within the semiconductor device (Figure 1).

The purpose of the P1687 or iJTAG initiative is to provide an extension to IEEE 1149.1 specifically aimed at using the TAP to manage the configuration, operation and collection of data from this embedded instrumentation circuitry.

The benefit. With the proposed IEEE P1687 standard, test equipment providers will be able to access the embedded instruments in the semiconductor devices for testing purposes. At the same time, electronics manufacturers will be able to regain test coverage with minimal cost impact by integrating this solution into their current test process. Here are some ways in which P1687 can be implemented on the manufacturing floor:

1. Integrated into existing ICT.

2. ICT system > P1687 test solution.

3. P1687 test solution > functional test.

4. Integrated into existing functional test.

Among the possible implementations for P1687, integration into the ICT system would most benefit manufacturers, as the majority of high-volume companies use ICT to screen structural defects. With this implementation, EMS companies would be able to increase the value of their ICT and avoid a costly investment in another system to cover both the analog and digital defects of the assembly.

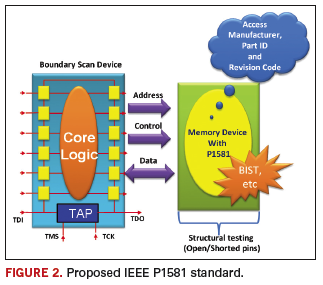

IEEE P1581

The challenge. One of the most common devices today is Dynamic Data Rate (DDR) memory, which can be found on everything from netbook motherboards to a larger high-end server and telecommunications boards. The challenge in testing memory devices lies in the high clock speeds for DDR memory, which now run in the GHz range. Again, with such clock speeds, testpoints would no longer be viable. The lost coverage means failures could only be captured after ICT, where finding defects and repairing them would be five times more costly.

The proposed solution. The proposed IEEE P1581 (Figure 2) aims to develop a standard method for testing low-cost, complex DDR memory devices, which would be able to communicate through another semiconductor device with an IEEE 1149.1 boundary scan capability. Presently, even if DDR memory devices adopt the IEEE 1149.1 boundary scan standard, this is still not a feasible test, as it will require the addition of the four mandatory TAP pins to the DDR device, which would add to the devices’ complexity and cost. P1581 would provide the protocol to access the test mode within the memory devices, without the need for dedicated test pin requirements. The defined standard for this new test technology would enable each vendor to create its own method for implementing test hardware functionality in memory devices. It guides them on the necessary implementation rules for access and exit test modes. In contrast to IEEE 1149.1, this standard provides a static test method and requires fewer test pins. The standard would also allow implementation of P1581 on other semiconductor devices besides memory devices.

The benefit. P1581 would help the DDR memory vendor to enable its memory devices to communicate with boundary scan-enabled devices. Manufacturers would regain the test coverage on DDR memory that even current standalone solutions like 1149.1 are finding hard to run with any good measure of stability due to high clock speeds.

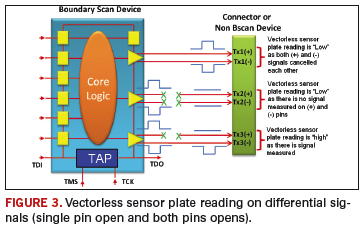

IEEE 1149.8.1

The challenge. High-speed differential signals, commonly known as SerDes (serial/deserializer) are reason to remove testpoints on assemblies. ICT has seen innovations to regain test coverage on connectors and devices connected to boundary scan devices without the need for testpoints by using a combination of boundary scan devices as signal driver and a noncontact signal sensing or vectorless sensor plate to detect opens and shorts on connectors, sockets and semiconductor device pins. However, this solution still falls short of being able to provide 100% coverage on differential signals. An example of failure escaping detection is when both differential signals (Tx+ and Tx-) are open, but the detected measured value of vectorless sensor plate will still be the same when both signal pins are properly soldered (Figure 3).

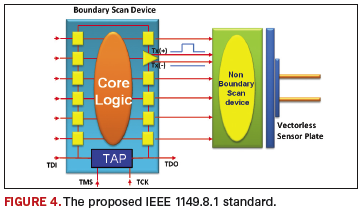

The proposed solution. IEEE 1149.8.1 entails a selective AC stimulus or differential signals, which when combined with noncontact signal sensing or a vectorless sensor plate, will allow testing of the connections between devices that adhere to this standard and circuitry elements such as series components, sockets, connectors and semiconductor devices that do not implement IEEE 1149.1 standards.

This standard specifies extensions to IEEE 1149.1 that define the boundary-scan structures and methods required to facilitate boundary scan-based stimulus of interconnections to passive and/or active components. This standard also specifies Boundary Scan Description Language (BSDL) extensions to IEEE Standard 1149.1 required to describe and support the new structures and methods (Figure 4).

The benefit. IEEE 1149.8.1 would enable selective AC stimulus generation that, when combined with noncontact signal sensing, would allow testing of signal paths between devices adhering to this standard and passive and/or active components. The biggest benefit of 1149.8.1 is that there is already a working solution currently implemented in some ICTs using a noncontact signal sensing or vectorless sensor plate that detects open/shorted pins on non-boundary scan devices and connectors connected to boundary scan devices.

IEEE 1149.7

The challenge. Assemblies, especially those used in consumer products, are pressured by shrinking form factors. In recent years, we have seen implementation of multi-core system-on-chip (SoC), multi-die packages on system-on-package (SoP), and package-on-package (PoP) devices. All these technologies pose new challenges when it comes to manufacturing test due to limited testpoints and higher speed. This is causing existing manufacturing test systems to lose test coverage, even with the implementation of IEEE 1149.1.

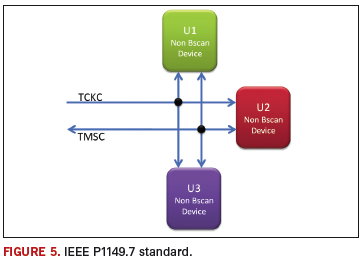

The proposed solution. IEEE 1149.7, also known as compact JTAG or cJTAG, is compatible with the traditional IEEE 1149.1 (JTAG) standard to provide an enhanced test and debug standard that meets the demands of modern systems. One unique feature of 1149.7 is the reduced pin count interface for the test access port (TAP) interface; it uses a two-wire interface, versus the traditional 1149.1 four- or five-wire TAP interface. Since IEEE 1149.7 is compatible with 1149.1, this proposed standard also permits four- or five-wire implementation (Figure 5).

With the adoption of a two-wire interface on IEEE 1149.7, devices on the IEEE 1149.1 standard will benefit from this, as it makes it easier for boundary scan to be implemented on complicated new package technologies such as SoC, SoP and PoP, which does not implement 1149.1 boundary scan chain using the standard four or five-wire TAP interface.

The benefits. IEEE 1149.7 would enable easier implementation of IEEE 1149.1 for SoC, SiP and PoP. IEEE 1149.1 implementation is limited to boundary scan chains, as it requires the connection of every TAP interface of every boundary scan device targeted for testing. In comparison, IEEE 1149.7 would simplify this by enabling a star architecture (Figure 5) more appropriate for SoCs, SiPs and PoPs. When used on SoCs, 1149.7 would enable testing and debugging of each core or chip in the package, using boundary scan in a single 1149.7 two-wire interface. This implementation is also possible on multi-die SiPs or PoPs. A key advantage of 1149.7 is that it can be implemented on through-silicon vias that would link each die through a via that connects the 1149.7 interface on each die to one another.

How successfully these proposed standards are adopted on the manufacturing floor depends on how well they will fit into the existing manufacturing test systems such as ICT, manufacturing defect analyzers and functional testers without impacting throughput, and while regaining maximum test coverage no longer available on the older testers. Another important factor will be the cost of the tools and their implementation.

Bibliography

1. Bill Eklow and Ben Bennetts, IEEE P1687 (IJTAG) Draft Standard for Access and Control of Instrumentation Embedded Within a Semiconductor Device, ETS 2006 embedded tutorial.

2. IEEE P1687 Working Group, http://grouper.ieee.org/groups/1687/.

3. IEEE P1581 Working Group, http://grouper.ieee.org/groups/1581/.

4. P1581 Working Group, “An Economical Alternative to Boundary Scan in Memory Devices,” January 2007.

5. IEEE 1149.8.1 Working Group, http://grouper.ieee.org/groups/atoggle/.

6. Adam Ley, “New 1149.7 Enhances 1149.1 Test Access Port, Maintains Compatibility for Boundary Scan,” Asset Connect, 2009.

Jun Balangue is technical marketing engineer at Agilent Technologies (www.agilent.com); jun_balangue@agilent.com.